History in the Making: Music Production in the Age of AI

AI is altering the world as we know today. Music, "the magical mirror reflecting parts of ourselves," and the status of its creator is now up for debates. What will become of music in the age of AI?

There is a lot to say about music and AI. As a PhD student immersed in reading, theorizing, programming, and experimenting with the latest developments of this new technological era, I am acutely aware of the profound transformations already unfolding in nearly every aspect of our lives. As an amateur musician who has studied some mathematical fundamentals of music, I cannot help but envision how these emerging tools might foster entirely new forms of musical expression, from reimagined tonal and rhythmic structures to custom-built virtual instruments and ambient soundscapes that glide seamlessly into harmonic melodies. In truth, the potential for innovation across all art forms seems vast.

Yet, as also someone drawn to post-Marxist critiques of society, I am also weighed down by the likelihood that these artistic ideals will remain niche, overshadowed by more commercial aims and never truly receive the public attention or dialogue they deserve. Nevertheless, I am beginning this article series with the hope of sparking conversation about how AI technology intersects with—and even challenges—the essence of art. I would prefer to sidestep the profit-driven noise that we are constantly nudged to accept and instead explore the deeper, perhaps more nuanced, possibilities of AI’s cultural impact.

To begin, I want to trace how we arrived at this juncture—examining how technology has reshaped our understanding of art through the lens of Walter Benjamin, who is one of the Frankfurt School’s pivotal thinkers. While I acknowledge the naiveté in Benjamin’s ideals of democratization through the mass reproduction of art, his foundational work on aura, the concept closely related to authenticity, remains invaluable for building a theoretical framework to navigate both the promises and pitfalls of art in our increasingly technological world.

At this point, although we have never met, I would like to express my gratitude to Sungjin Park for his article The Work of Art in the Age of Generative AI: Aura, Liberation, and Democratization. His work served as a Swiss Army knife in my efforts, helping me uncover numerous connections between key ideas.

The Tech-Informed Evolution of Music as Art

From the Renaissance onward, Western art was largely shaped by prevailing power structures, rendering most works primarily accessible to society’s upper classes. Although the rise of public exhibitions and concerts gradually broadened access to art, an elitist mindset persisted, as control over artists was predominantly held by the Church, the state, or affluent patrons. Art remained a tool for reinforcing social hierarchies, with limited opportunities for creators outside these structures to share their work. This exclusivity also shaped the perception of artistic value, often tying it to rarity and privilege. The invention of analog recording devices in the 19th century helped to alleviate this inequality. In music, Thomas Edison’s invention of the phonograph and the subsequent rise of record production fundamentally altered how audiences experienced sound. Parallel developments across various art forms underscored how reproducibility paved the way for a more democratized artistic arena.

However, these developments also called into question the inherent qualities of such reproductions. For a broader theoretical perspective, one inevitably turns to the Frankfurt School—particularly Walter Benjamin and his seminal essay, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. In examining the distinction between an original artwork and its copies in both cultural and technical contexts, Benjamin introduces the concept of aura. He defines aura as the unique presence of an artwork, derived from its singular existence in time and space, its embedded history, and its unrepeatable here and now.

This concept closely aligns with the notion of authenticity, referring to the material originality and historical presence of a work. While authenticity is anchored in the physical and historical singularity of an artwork, aura extends to its intangible, almost mystical qualities that evoke a sense of uniqueness and emotional resonance. Though interlinked, both concepts recede in the era of mechanical reproduction, as repeated exposure to copies reduces the necessity of the original works. Benjamin termed this phenomenon the liquidation of aura, signaling a profound shift in how art is perceived. In the realm of music, while live concerts exemplify aura through their unique, unrepeatable nature, recorded music fosters mass dissemination and standardized listening that detaches performances from their original context and often establishes a single canonical interpretation.

Beyond aura, Benjamin also underscores the transformative potential of mechanical reproduction. By making artistic works more widely accessible, mass production democratizes culture and nurtures a more inclusive public sphere. According to Benjamin, this evolution erodes the once-rigid boundaries between art producers and audiences, granting the public a more active role in interpreting, criticizing, and shaping artistic content. In music, for example, the proliferation of recorded performances not only expands the listener base but also spurs critical engagement, bridging social divides and reconfiguring how the public interacts with artistic productions. Ultimately, such widespread accessibility encourages a more participatory culture, promoting open discourse and collective engagement with art.

From CDs to Music Dematerialized

With the advent of compact discs (CDs) in the 1980s and, crucially, the rise of MP3s and file-sharing platforms in the late 1990s, music underwent a second revolution in reproducibility. This era of digitalization introduced us to the phenomenon of dematerialization and effectively ended the aura of a physical artifact. Through sampling and remix culture, and later Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs), the notion of a singular, captured musical performance—akin to a live analog recording—gave way to meticulously engineered, composite productions. By the 2010s, the introduction of Virtual Studio Technology (VST) and highly realistic instrument emulators further revolutionized music production, liberating it from reliance on physical instruments altogether—an evolution facilitated by the inherent limitations of human auditory perception within a certain frequency range.

SHEER Magazine is Free Today. Still, Your Promise in Help Goes A Long Way for Independent Journalism in Turkey

From a Benjaminian perspective, this second revolution represents an intensified liquidation of aura, while also shifting its focus to performance and production. Historically, live performance carried an aura because it was unrepeatable; no two performances were identical, and the shared presence of performer and audience in a single space constituted a unique encounter. Despite the dissolution of aura in reproducible media, large-scale concerts and real-time online music events continue to immerse listeners in a communal aura—an intensity derived from thousands of people experiencing the same music simultaneously. Moreover, the digital era has facilitated novel communal music practices, including avant-garde live coding sessions, illustrating how aura can be reimagined through collective, real-time engagement. This indicates a shift in how aura is generated: from the singular artifact to the communal experience.

As a side note, the growing popularity of vinyl records—often considered to have lower audio fidelity than high-resolution digital formats such as FLAC—reveals an intriguing material dimension of aura. Some attribute vinyl’s renewed appeal to nostalgia, yet its ritualistic use and maintenance, alongside its inherent imperfections, embed it in a distinct physical context that imparts a unique history to each copy. In this sense, the medium itself contributes to the aura of the listening experience. A parallel can be drawn with the enduring appeal of physical books, suggesting that tangibility and ritualistic engagement continue to shape how cultural products are experienced and valued.

The Rise of the AI Age

Advancements in the microelectronic chip industry and the dramatic increase in computational power transformed the tech landscape. Parallel computing techniques, adopted in the late 1990s for game production and 3D rendering, played a key role in this transformation. These developments brought renewed practical potential to the once largely theoretical field of machine learning and neural networks, whose roots stretch back to the 1950s. The first major breakthroughs appeared in the 2010s, driven by deep learning models that efficiently handled large-scale matrix operations. This progress was bolstered by NVIDIA’s CUDA framework for parallel computations and further accelerated by programming libraries such as TensorFlow and PyTorch, enabling the widespread application of AI across numerous disciplines.

In 2018, the introduction of the transformer architecture sparked another revolution in deep learning. This approach significantly expanded model capacities, allowing systems to learn from massive datasets while mitigating the issue of catastrophic forgetting. In the following years, we saw the emergence of so-called foundation models, featuring flexible architectures adaptable to a range of tasks—from programming assistance and text refinement to chatbots, semantic segmentation, and object detection.

Alongside advances in computational power and model architectures, new learning paradigms (e.g. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Diffusion Models) have enabled the generation of entirely novel outputs. These developments are reshaping the creative landscape, leading to a surge in AI-generated art, including music production that has become widely prevalent in the recent past through platforms such as SunoAI, Jukebox, and MusicLM, which demonstrate how these technologies can compose new musical works.

Music Generation in the Age of AI

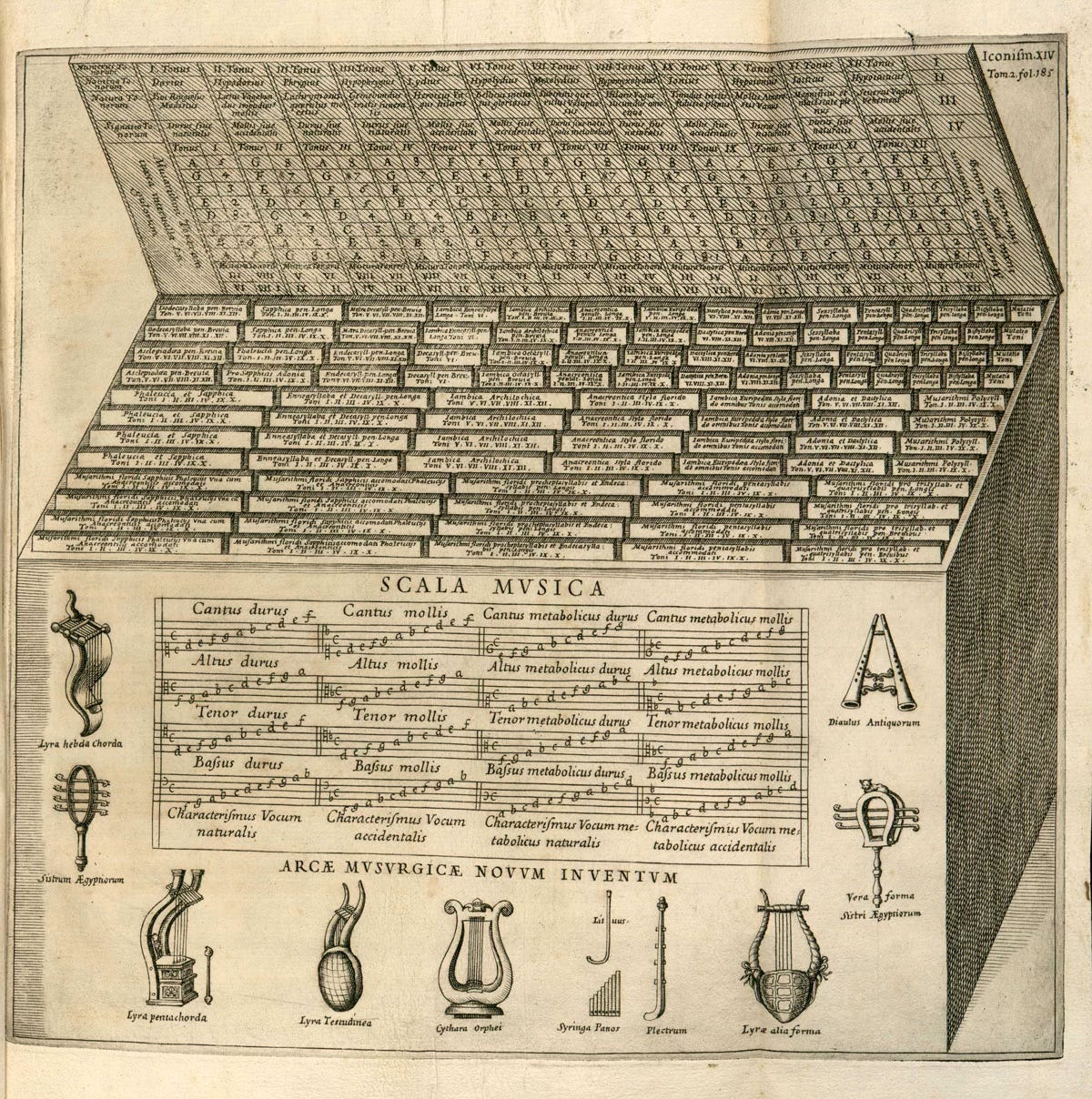

From a technical perspective in the domain of music, we can divide music production into two main parts: writing a new composition and performing an existing piece. Although realistic-sounding VSTs have partially achieved the second goal (despite limited vocal components and requiring some adjustments), composing original music presents a more complex challenge. Historical efforts in algorithmic composition date back to at least the 17th century, when German Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher designed Arca Musarithmica to guide non-musicians in producing church music. As Western music theory incorporated elements of modern algebra, employing various mathematical concepts like graphs and groups, it revealed certain patterns that could be used for algorithmic composition. In this context, pre-AI composition tools often depended on carefully crafted assumptions, whether based on mathematical principles or a particular composer’s style. Even though they relied on data, the first successful AI composers—such as Deep Bach and MuseNet—were designed with similar goals in mind.

A fundamental distinction between these pre-AI algorithms and current generative AI models lies in how their outputs are produced and understood. While non-data-driven methods can appear complex or even completely random, their operations are ultimately traceable. By contrast, the data-driven nature and computational scale of deep learning can yield unpredictable yet reasonable outcomes. It is worth noting that some research teams are investigating how these models work. However, a comprehensive theory that deciphers deep learning’s processes remains elusive, and existing explainability methods are generally tailored to specific datasets and models.

In this sense, even though pre-AI approaches to both composition and performance became publicly available in the early 2000s, using them effectively still required expertise in multiple fields, leaving the practice niche and somewhat avant-garde, and acting as a barrier for novices. The advent of AI-generated music removed many of these hurdles and allowed general users to produce complete pieces that are both composed and performed. Today, a vast array of possibilities is accessible through simple text prompts, which removes creators’ dependency on specialized technical knowledge in music production. Furthermore, generative AI models lets users incorporate various inputs—such as an existing composition, an image, or other representations of information—throughout the generation process, expanding creative opportunities for anyone interested in exploring AI-driven music.

Under this new paradigm, it is crucial to understand how the AI revolution is fundamentally different from the technological shifts that previously shaped the art world. Until now, advancements in pre-AI technologies expanded the possibilities for producing and experiencing music, as well as streamlined the processes of publication and composition-without directly affecting the subjective decisions that shape the final work. In contrast, generative AI models introduce complex, mostly opaque, yet consistently executed interpretations of user inputs. These models handle both the compositional and performative aspects of music, requiring significant time and careful attention to factors like style, instrumental capabilities, and intended audience.

In that regard, Sungjin Park's aforementioned paper, The Work of Art in the Age of Generative AI: Aura, Liberation, and Democratization, sheds light on how AI reshapes both the production and perception of art by offering a contemporary approach grounded in three main concepts: aura, liberation, and democratization. Each concept reflects how generative AI is altering the fundamental roles that art plays within culture. In the following discussion, I will concentrate on the first two concepts—aura and liberation—as they most directly illuminate how generative AI reshapes the creative landscape.

Pushing the Buttons: Generative AI at Play

From the audience’s perspective, an artwork's aura evokes a sense of awe and reverence. These feelings are not solely about the artwork itself but are deeply tied to its context, specifically to the familiarity we feel between our own identity and the artist. The works that move us most deeply us often address the values we hold, some of which we may not even be consciously aware of. This emotional connection elevates the artwork from a mere commodity to something more profound—an almost magical mirror reflecting parts of ourselves.

Generative AI challenges the assumption of the human artist by presenting an algorithmic chimera, an unholy blend that mimics the historical endeavors of human creators. AI-generated art merges the visions of past artists in ways that seem "unnatural" and in certain situations, can fail miserably. For example, the SunoAI v2.0 completely misinterpreted my intention of generating a scary atmospheric sound:

Nevertheless, we see the outputs becoming more believable with each new version. Here is the result of the same prompt by SunoAI v3.5:

In this instance, even a nonsense prompt can generate a completely novel, somewhat original piece. Here is Nonsense, a song produced from my prompt “speaking nonsense, japanese turkish arabic music,” courtesy of SunoAI v3.5:

This outcome resonates with Park's more optimistic framework. He proposes that, when infused with human input, generative AI can create a new aura by emphasizing unexpected novelty rather than context. This shift encourages the notion that art's aura can evolve to reflect the “dynamic interplay between machine capabilities and human creativity”, eventually resulting in Co-creativism. The artist increasingly appears as a cyborg—someone whose creativity merges with AI’s algorithmic power, granting aura not just to the individual but to the collective hybrid process.

Park argues that a new auratic experience emerges for human artists throughout the creative process, especially when we avoid treating generative algorithms as sole creators. In this model, the artist and the algorithm collaborate through a back-and-forth dialogue. This synergy between “human intention and algorithmic interpretation” creates a dynamic that challenges traditional notions of authorship.

Consider Nonsense: as the “human artist,” I had no idea what “japanese turkish arabic music” might sound like. After the piece was generated, I recognized certain characteristics of the genres, and SunoAI’s interpretation revealed potential points of connection. Moreover, I could refine the version I found most compelling and further explore its possibilities, as shown below:

This interplay between artist and machine highlights the educational benefits of the process—where output inaccuracies in the artist’s input are not mere algorithmic failures but mirrors of the artist’s limited knowledge or incomplete vision. Through collaboration, there is room for the artist to grow, recognizing that missteps indicate areas for development, making the experience both creatively and personally transformative.

Conversely, artworks generated in unstable or experimental settings often emphasize the algorithm’s “unnatural” qualities more sharply, which can create a mental burden for the human artist. In Baudrillard’s terms, encountering such simulacra without a coherent, hyper-realistic context can be disorienting and leads to “intoxication.” In these scenarios, the artist becomes a “naturalizer,” grappling with the algorithm’s complexities while protecting their own mental well-being.

Unfortunately, this is quite difficult to achieve with commercial AI music generators, where companies often avoid such outputs to retain customers. Yet, I attempted to produce a form of AI-scat with SunoAI v2.0 (watch out for the jump-scare at 0:42):

Frankly, inputting random prompts to see the possible “intoxication” was also intoxicating. By contrast, stable, default settings tend to yield bland results, essentially inauthentic yassified clichés. One could use such artworks in an ironic, kitsch manner, but prolonged exposure may harm an artist’s vision—especially for novices—by stifling critical thinking and leading to “taste-numbness.” This default preference for stability, often driven by commercial interests, aligns with the low-art concept of the Culture Industry.

To illustrate this, I conducted a small experiment: using ChatGPT as a music-to-prompt converter and lyrics writer, I attempted to generate a song inspired by The Weeknd. To get the best results, I used the latest version of SunoAI (v.4.0). I believe no further comment is necessary:

In short, the tension between stability and unpredictability in AI-generated art relates to the bias-variance trade-off in machine learning, often leaving artists torn between intoxication and taste-numbness.

Liberation or Subjugation: AI’s Human Expense

Another key concept is liberation. Park focuses on two related concepts: “liberation from subjectivity,” which underscores the communal aspect of art, and the paradoxical notion of “liberation from (individual) liberation.” He draws on Gadamer’s hermeneutics to emphasize the audience’s role in completing an artwork’s meaning. Because the algorithm possesses vast knowledge of the artistic landscape, the artist can venture into entirely unfamiliar territory. For instance, it’s easy for me to generate Chinese folk music with SunoAI v.4.0:

It may well lack elements of traditional Chinese folk music—perhaps another form of yassification—but the result remains entirely foreign to me. I have no idea what the song signifies or the nature of the instruments used. However, we can assume it carries deeper meaning for a Chinese listener. This distances the human artist from the shared knowledge between the algorithm and its intended audience. Consequently, the artist may have little or no understanding of that intersection, leading to a sense of alienation from their own work—a concept echoed by Barthes’ “death of the author.”

Although this is a specific instance, it’s not hard to see how it could resonate throughout a longer creative process. Under algorithmic influence, the human artist may be “both emancipated by and subjugated to the capabilities of AI.” This dynamic disrupts subjectivity, once central to modern thought, and can render the artist a passive observer. With a clear vision, one might step into the role of curator or editor, yet the sense of alienation can persist. On a more philosophical level, a powerful AI model can take on the quality of a “digital deity,” making humans increasingly dependent on it. This “liberation from liberation” paradox can ultimately lead to the singularization of thought over generations, leaving humanity in a conceptual space of “hyperthoughts,” a wasteland of simulacra warped from what once was genuine thinking.

Of course, this dystopian vision remains far from our current reality and may never fully unfold for those who continue to value subjectivity. Even with cutting-edge technology, so-called digital deities are often dull to experienced observers and find direct use mainly in commercial settings. While these developments will undoubtedly affect society’s economy, seasoned art enthusiasts may regard such AI models as a “continuous library of mediocre representations”—a useful toolbox with minimal potential to truly reshape our deeper thought processes.